It’s fashion week and they are eagle-eyed. As the show begins (live via social media) so too do their gripes. They declare they’d never wear such a garment. They announce they’re repulsed, bored or bewildered by the styles. They might claim to have “seen this all before” or that Largerfeld or Elbaz or Westwood did it better. They might compare the clothes to circus costumes or to their grandmother’s wardrobes, adding #whathappenedtofashion for rhetorical effect.

They are, of course, not the journalists paid to write about the latest in seasonal style. These are the armchair critics, the at-large purveyors, the mad @tters whose scrolling and trolling often lead to ranting about the absurdity of haute couture or the redundancy of prêt-à-porter. And while opinion tussling over mode du jour is nothing new (and an integral part of cultural balance) what has changed is the swiftness of the kicks and the very public platform.

Where once collections were presented to the world beside sufficient explanation in the days, even weeks, after the event they are now beamed to all corners of social media in real-time—giving us all front-row passes. And unlike film, music or theatre, the fashion runway offers no preview to prime audiences and they are given little to no prior understanding of the intention. All they have is the execution at face, or rather livestream, value.

In the case of Lionhead-gate, also known as Daniel Rosebery’s Schiaparelli spring/summer 2023 haute couture collection, the role of intention and execution met a drastic crossroads. The creative director presented a homage to part one of Dante Alighieri’s 14th Century epic Divine Comedy, Inferno. Within the poem, three beasts appear—the lion, the leopard and the she-wolf—as prophetic apparitions which the protagonist must overcome. Rosebery romanced the idea with a most Schiaparelli façade – distorted silhouettes, extravagant embellishment and plenty of surrealist pomp and ceremony but, most literally, he celebrated its image by manufacturing artificial heads of the bestial metaphors onto three of the collection’s gowns.

With the image of taxidermy fixed to glamorous couture and none of the back story, the looks sent shockwaves across social media in minutes. Worn on the runway by Irina Shayk, Shalom Harlow and Naomi Campbell, and again on the red carpet by Kylie Jenner, it drew too close to a trend for skinned minks or big-game hunting. And despite, or perhaps because of, the elaborate precision of the Schiaparelli ateliers (the heads looked nothing short of absolutely real) any theatrical symbolism was lost and PETA was tagged.

“@schiaparelli RIP Aslan.”

“@schiaparelli There’s nothing fashion about pretending to wear dead animals.”

However, in the days that followed, the president of PETA, Ingrid Newkirk, did not denounce Rosebery’s inspiration, concluding that the looks “celebrated lions’ beauty” and that it was actually “fabulously innovative”. Her anti-conspiratorial take on the concept flailed the fist-wavers and the comments sections were soon overtaken by those defending his artistic connotation.

“@schiaparelli Couture is literally an art, it does not need to be 100% understood and approved by the masses. As long as there is no animal cruelty involved, let the artist express himself.”

There is something unique about the public’s reaction to fashion in comparison to other artistic mediums. Perhaps it’s because the sartorial genre is parked in two distinct spaces—one that is a fundamental human necessity (ie. the clothes on a person’s back) and another that is a radical, albeit exclusive, expression of modern design. This disconnect acts as a soapbox for keyboard warriors who are quick to take offence or forge unfounded conspiracies. And, for those subscribing to the #fashionsgonemad ideology, designers are the ones drawing the blasphemy sword.

“@dietprada Awful! So-called “fashion” has become an absurd mockery of demonic propaganda”

Of course, Schiaparelli isn’t the only one on the receiving end. Most designers who choose to merge art or social issues with their aesthetic are met with head-scratching from the wider community. The thing is, we’re not always meant to “get it”. When Viktor & Rolf presented their spring 2023 collection in January, their use of sideways and upside-down ball gowns challenged the status quo in a facetious, unsettling way, and it was met with the expected grievances.

“@viktor&rolf What the hell is going on?!”

“@viktor&rolf Between this and the stuffed animals, fashion houses are going crazy if you ask me.”

Cavilling modern couture has long been something of a lowbrow sport. Not unlike the kid in art class who repeatedly exclaimed he could have painted The Scream if he wanted to, it seems online commentators just love to hate. Yet, it’s not only the more esoteric corners of high fashion that stir the trolling pot. While haute couture tends to draw the most obvious attention, mainstream luxury has also seen a rise in social chatter. Everything from creative director announcements to company mergers to label acquisitions has become zeitgeist gossip fodder. Those who follow Insta-vigilantes Diet Prada (run by Lindsey Schuyler and Tony Liu) will be well-versed in the ever-dramatic ins and outs of the industry as well as the snap-quick comments from their fashion aficionado followers. The comments-warriors on pages like these are sartorial almanacs, knowing their Micheles from their McQueens, their Vaccarellos from their Tiscis. And they take no prisoners when it comes to calling out derivative design, cultural appropriation or unsatisfactory collections. In 2019, their screenshots of Stefanno Gabbana’s racial tirade resulted in a US$600million damages lawsuit against the Instagram duo.

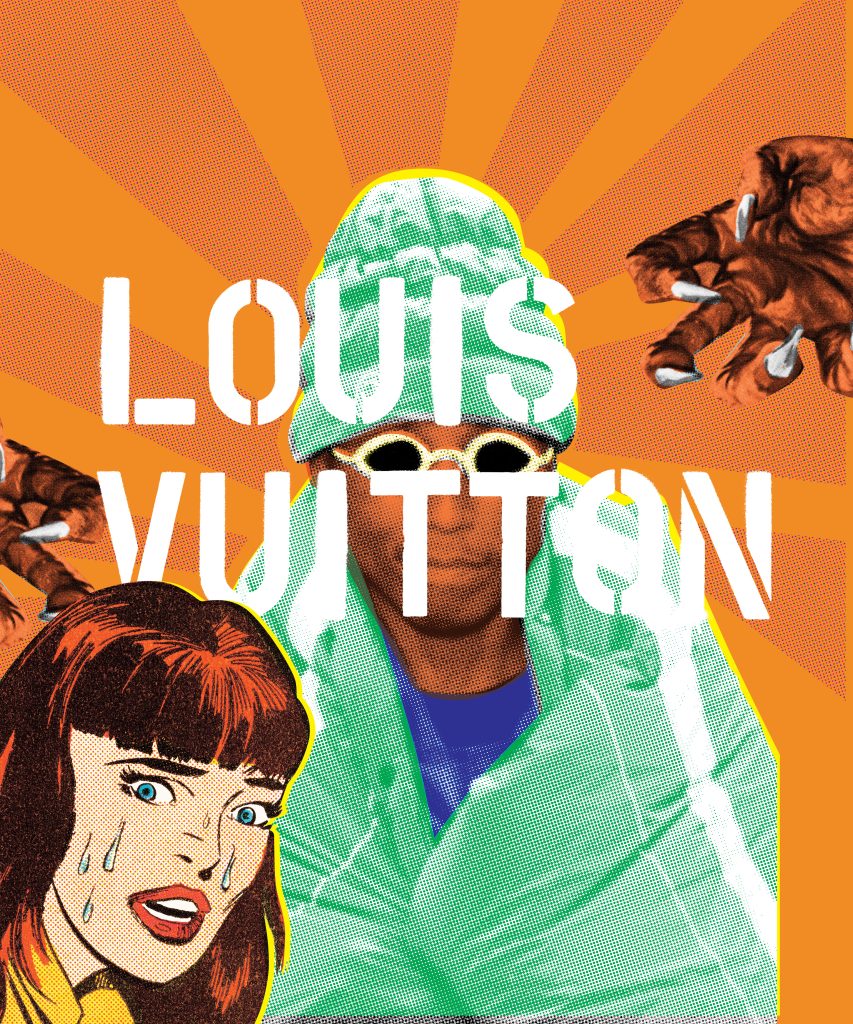

Zeitgeist accounts such as this (as well as mainstream fashion sites) have created a community for the online sub-genre of unofficial industry experts. Their comments wells have become a meeting place for those preempting matters of the style business. In February of this year, when Louis Vuitton announced singer Pharrell Williams would succeed the late Virgil Abloh as creative director of menswear, gossip went into overdrive. While many decided it was a genius marketing decision, a disproportionate amount called out the label for choosing a celebrity name over a traditional designer.

“@louisvuitton And next: Drake for Gucci.”

But does it matter? Do comments trends reflect actual sales trends, running parallel with market value and consumer interest? In the case of Chanel, where online fanatics express constant complaints over the post-Lagerfeld era, you could be forgiven for thinking the brand might be out of favour. However, in the two years following Karl Lagerfeld’s death, when Virginie Viard became creative director, Chanel’s profits increased by more than 22% with record sales across all categories*. If this is a trend, then it seems online opinion produces little more than hot air, and from people who are mostly unlikely to be customers anyway.

In addition to Williams, the industry has announced two other major appointments for this year. Daniel Lee, whose tenure at Bottega Veneta ended in 2021, has moved to Burberry, while Valentino alum Sabato De Sarno will take over from Alessandro Michele at Gucci. The comments cowboys were quick to cast their opinions, with the rhetoric around mourning the exit of wunderkind Michele and excitement over Lee’s ability to “save Burberry” (though his decision to remove the current ‘serif-font’ logo and return to its heritage was a divisive start).

Marie-Claude Mallat, the owner of the Australian public relations agency MCMPR, explains that the teams behind the designers do need to realise there is weight in social media’s influence. “Since the rise of social media, we have seen brands adapting to larger resource bases—time and people—to manage social media in general. A part of this is social listening and comment monitoring. They monitor both positive and adverse commentary.” she told GRAZIA. “[But] there really isn’t one single best approach for all situations. Brands need to assess the comments and evaluate the best course of action. Some of the questions we ask when commentary is adverse is, is there merit to the feedback? Does the brand have a social responsibility in this particular situation to its community to respond or repair? So it’s a case-by-case assessment.”

After the Schiaparelli incident, Rosebery remained mum on the backlash. In the immediacy his silence drew criticism, yet as time went on it seemed the best approach. However, when labels are accused of more troublesome antics (Balenciaga, Yeezy and Alexander Wang have all recently caused news-worthy controversies) comment riots are an understandable fallout—and force designers to face the music. In these cases, social commentary is invaluable in not only calling out the infractions but likely to help reduce toxic behaviours in the future.

Mallat agrees that depending on the situation, conversation from the community can be constructive. “Many brands have, in fact, found the immediate feedback very helpful. Their community’s engagement with collections, specific items and campaigns give the brand a read on what has worked. This can impact decisions made around production levels and quantities. With the right approach to production management, this can reduce waste but also maximize the brand’s opportunity to fill the demand.”

There’s no doubt that designers today live in a particularly Gogglebox time—they are publicly exposed to the opinions of people who aren’t necessarily customers but are heavily engaged in their process. People who have the potential to reach the eyes and ears of millions of others. With this in mind, there are also many designers using this exposure to their advantage, with some even designing purely to gain notoriety from the masses (the Big Red Boots – those gigantic cartoon-shaped boots all over TikTok—by New York art collaborative MSCHF, have reportedly already completely sold out). Whatever the designer’s intention, however, there’s no question that they are much more likely to consider social repercussions than their predecessors ever would have.

Nearly three decades ago Alexander McQueen presented his fall/winter 1995 collection entitled The Highland Rape. It was an oeuvre of rebellious tartan suits, nipple-baring lace gowns and punked-up Scottish kilts. Shocking and aggressive, its name was meant in a military sense—the colonisation of his ancestral home of Scotland by England during the Highland Clearances of the late 18th century—and it had nothing to do with sexual assault. While today the term would be taboo in any context, had McQueen presented this collection alongside its title now (and without explanation) it’s likely he would have been cancelled for good.

Today, finding a balance between artistic freedom and social responsibility is a very public matter for designers, and deciding when to listen and when to ignore can be challenging. When Elsa Schiaparelli first began including eccentric appliqué and surrealist art in her designs in the 1930s she was met with plenty of conservative criticism. Had her critics’ influence been louder and more visible the subsequent future of her label might have been very different.

But it’s not all bad. Even given today’s heavily criticised industry, there are moments that welcome unanimous applause. Most recently, Haider Ackermann’s guest couture collection for Jean Paul Gaultier was universally lauded for its decadent, respectful elegance as was debut designer Rahul Mishra (the first Indian to show on the official couture schedule) whose distinctly innovative show revealed a totally appreciated return to supreme construction.

But perhaps most pertinent was the announcement of the impending return of Phoebe Philo. The leader of minimalist high fashion who left an #OldCeline-sized hole in the hearts of industry die-hards with her exit in 2017, is returning with a namesake label. A barrage of “she’s coming to save fashion!” and “God Bless The Queen!!” comments ensued. It finally seemed there was something everyone could agree on.

“@phoebephilo Okay, but what’s with the bold serif logo font?!”

Guess you can’t please all the people, all of the time.

*Chanel Limited financial results for year ending 31 December 2021