HIGH GLOSS

The condition of clothing can say a lot about a wearer. Historically, the less marred your clothing, the higher your status likely sat. And up until the middle of the 20th century, shiny, box-fresh pieces in mint condition that told the world you were not of working class, were revered as the pinnacle of fashion. Attire universally considered covetable consisted of pieces that gleamed, where premium craftsmanship and ornate detailing screamed of the money spent. The appeal may seem straightforward—why wouldn’t you want a new bag to look new? Today, however, the concept goes a little deeper than that.

While it’s a given that designer items are generally of better quality than their high-street counterparts, there is a visual element that is an inherent part of the purchasing experience. Particularly for those for whom buying designer is a sporadic luxury, perceived “newness” can be of utmost importance. On a more base level, it can help consumers to feel justified in parting with hard-earned cash. The price of luxury clothes, shoes, and accessories can be exorbitant for the average earner, and many who still choose to engage with this level of fashion may need to save up for a long time before biting the bullet. When the stakes are higher, there is a tangible expectation that reflects the investment. Of course, this also speaks to the need for long-lasting appeal. Polished pieces can be passed down or resold if they maintain a certain level of quality and timeless allure. In this sense, investing in what could be considered ‘obvious’ designer luxury not only justifies the initial cost but can actually snag smart buyers a profit if the resale market is kind, extending the value of the splurge, even multiplying it.

Read more: 15 Standout Timepieces from Only Watch 2023

Take the culture of contemporary sneakerheads. A subgroup of footwear puritans who carefully oversee their collections of high-value sneakers, all shrink-wrapped to prevent any hint of mould or wear as they sit on display, never to feel the gritty brush of cement or dirt. As one budding sneaker hobbyist describes privately, “It’s not about your personal style, I don’t even want to wear these sneakers. It’s about curating a collection the same way museums curate works of art.”

“Preserving a rare pair of [Air] Jordans is like preserving a piece by Da Vinci.”

Though not all in the camp of mint fashion go as far as this to upkeep their polish, the collectability element plays a major part in influencing those who seek out pristine goods. Other styles may have their time in the spotlight, but bypassing the trend cycle in favour of these perfect pieces means committing to what will likely be held as a premium throughout the years. Especially as we see sites like TheRealReal, Vestiaire and Grailed boom, the question of a product’s resell capabilities is usually a no-brainer when it still looks box-fresh.

IN DISTRESS

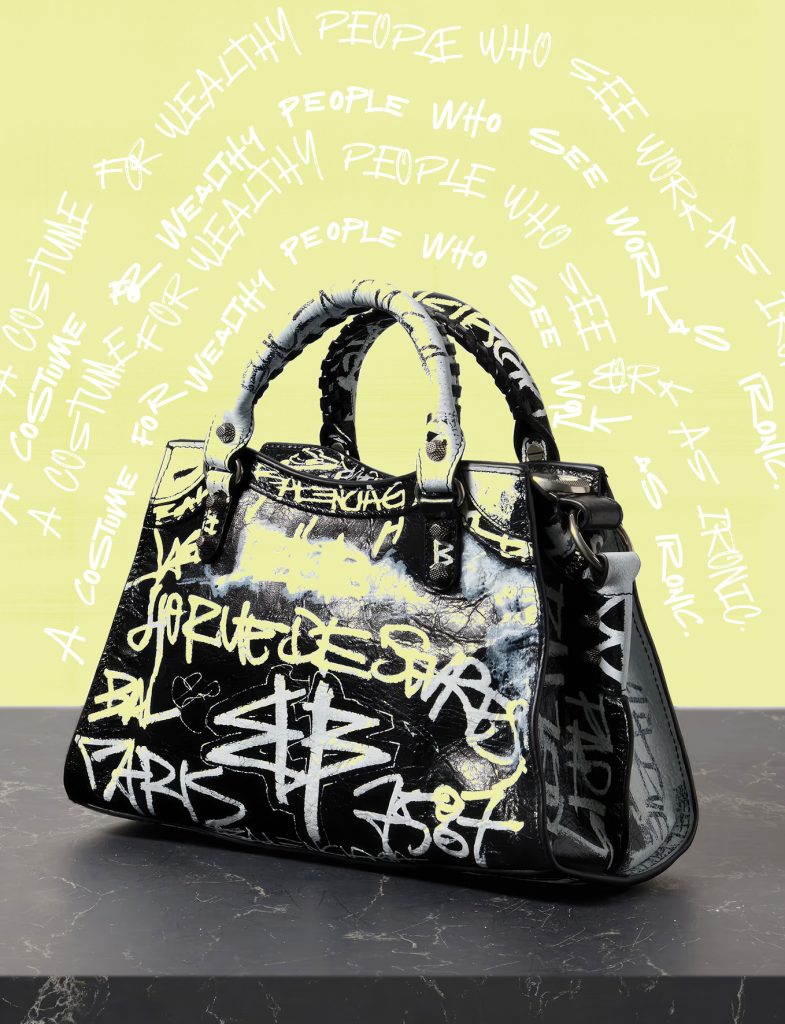

In the spring of 1990, Maison Margiela ruffled feathers with a pair of Tabi boots that were covered with layers of thick white paint intended to crack more and more over time. While the general consensus at the time was that it was an ingenious creation, a similar controversy stirred fashion followers again in 2022 when Balenciaga released its shredded iteration of the Paris sneaker. The heavily mauled shoe with the brand’s faded logo plastered on the side spurred many to beg the question: has it all gone too far?

While only a select few would drop a few grand on the mangled trainers—only 100 were made around the world—the idea of throwing your entire salary at footwear that looked like it had been thrown into a wood chipper is a perplexing concept. Examples like these may seem like the more extreme behaviour of die-hard fashion fans, but the trend of distressed fashion can be found just about everywhere—and it’s not as simple as taking some scissors to perfectly good clothes.

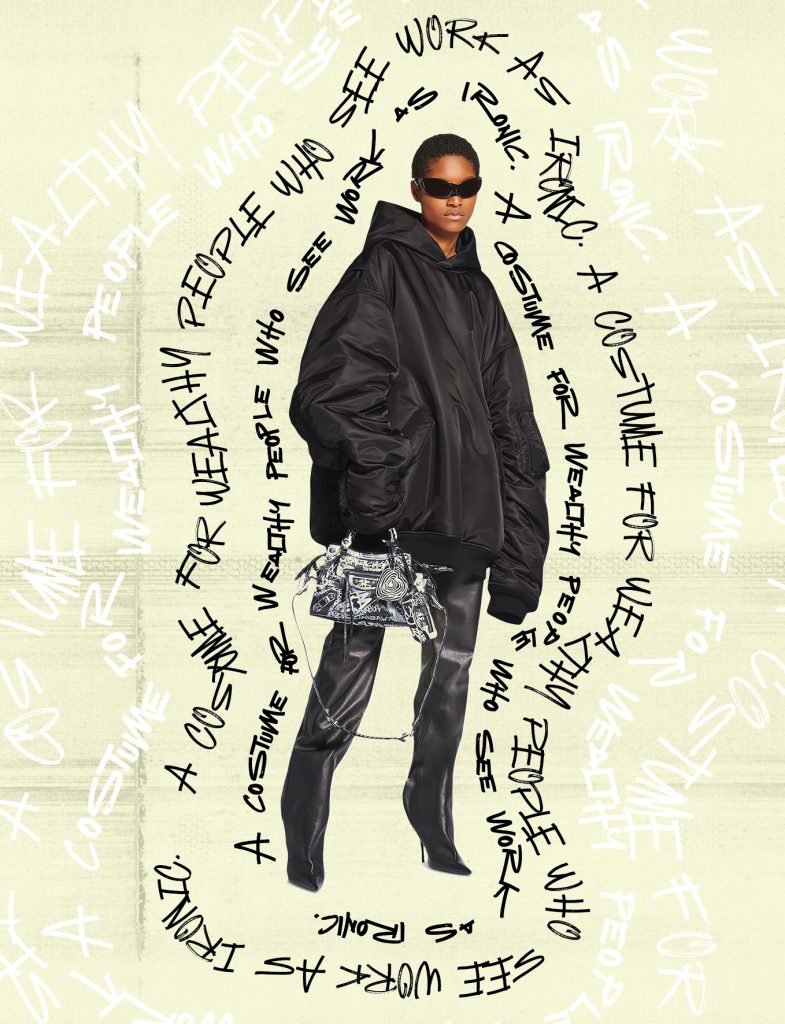

From Vivienne Westwood to Rei Kawakubo, distressed fashion holds its power in the intentionality of its damage. It plays on ideas of imperfection or “ruined” clothing and intricately replicates these qualities through astute garment-making techniques, all in the name of making a statement—or rather, a lack thereof. As Kanye West once infamously noted, “No one wants to look like they’re trying too hard”. And what says ‘I don’t care’ more than a $2,700 pair of shredded sneakers?

But beyond the cool factor, there’s a psychological value that worn-in clothes can hold. Not only do they evoke nostalgic feelings of heirlooms, but they also bestow an element of intrigue to the wearer. Whether it’s a faded wash, slouchy silhouette or carefully-placed tears, damaged goods offer us an elusive sense of character and individuality. Clothes suddenly become unique and subversive, and they certainly don’t look like they’ve been mass-produced and purchased in bulk, even if they have.

Read more: Who Invented the Original Barbie Doll?

In his 1899 book The Theory of the Leisure Class, economist Thorstein Veblen linked the distressed look to ‘inconspicuous consumption’, where people were hesitant to appear well-off to the masses. In the modern age, luxury consumption has expanded so much that a willingness to wear tarnished pieces has arguably become the very height of luxury.

Understandably though, the look has garnered some considerable backlash for the morally questionable idea of “dressing poor”. In her 2010 thesis, Kate Louise Rhodes points out how a wearer can “choose to dabble” with the look of the working class, with distressed clothes able to “foster the illusion of work”. While second-hand and worn-in clothing isn’t a choice for some, Rhodes explains that they can serve as “a costume for wealthy people who see work as ironic”, and who get to take off the costume at the end of the day.

But the return of grungy fashions could spell a win for the environment, too. As GRAZIA Australia’s Fashion Director, Aileen Marr, explains, the trend sheds a new light on previously-untouched thrift stores. “I’m loving this revival of ’90s counterculture to buttoned-up fashion,” she enthuses. “Its return speaks to the need to recycle clothes during a time when the consumption of fashion has become maxed out.”

“It’s an anti-conformist fashion statement on the one hand, but also a meaningful movement as well.”

This story first appeared on GRAZIA Singapore.