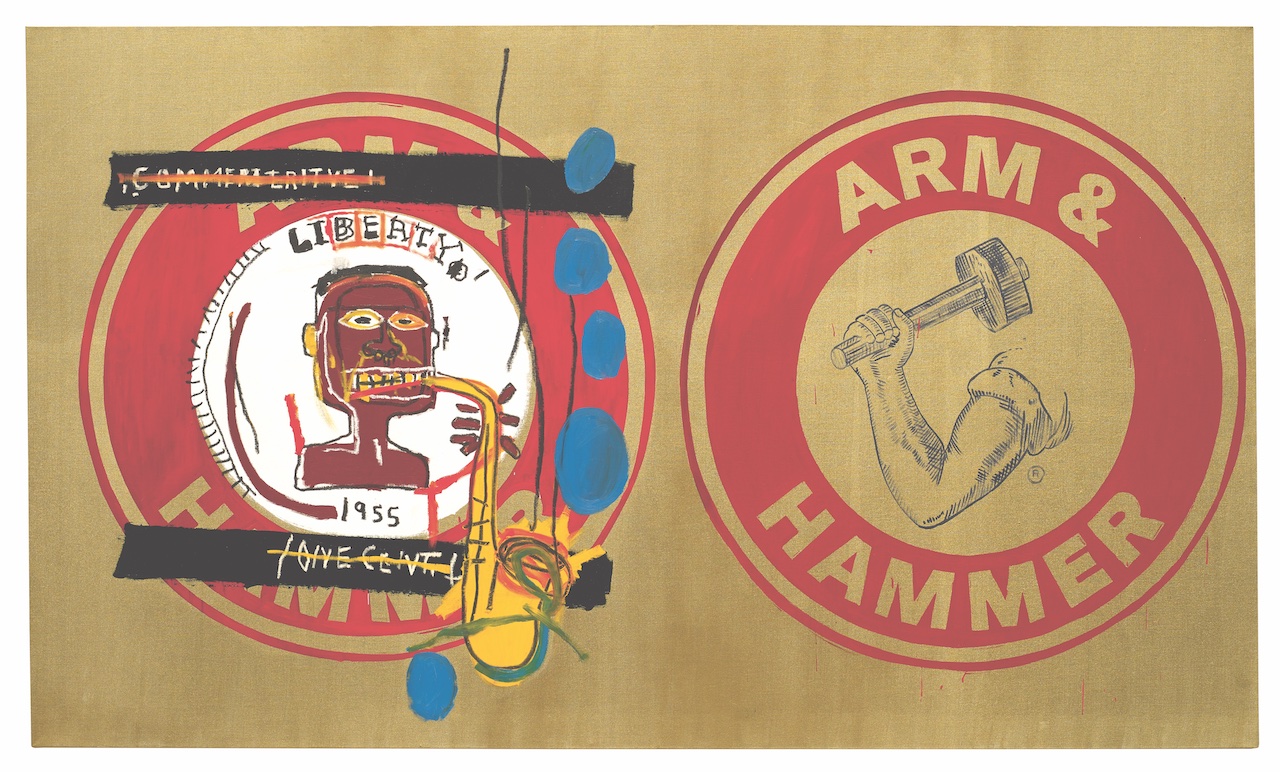

Arm and Hammer II, 1984-1985, Acrylic, Silkscreen and Oilstick On Canvas, JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT & ANDY WARHOL

Nearly 30 years after his death, Jean-Michel Basquiat broke all records to become the most successful American visual artist in history. But during his lifetime he also broke racial barriers, and stereotypes and inspired a generation of young Black artists. His experience was rich and volatile, he was a dreamer that lived fast and free and now, the Louis Vuitton Foundation presents a rarely-seen retrospective of his infamous collaboration with friend and mentor Andy Warhol. This, in addition to a growing global presence, makes his brand, and life, an unending subject of fascination. But who was Jean-Michel Basquiat? Was he the curious celebrity who befriended A-listers, fronted magazines and made a fortune? Or was he the genius neo-expressionist who strived to change the culture of art? Perhaps he was both.

Jean-Michel Basquiat knew he would be famous. By all accounts, the artist, whose oeuvre of maniacal postmodern paintings now fetch in the financial ballpark of Picasso, Cézanne or Gauguin, had an omnipresence destined for greatness.

Read more: Is There Hope for the Malaysian Film Industry?

By the time he died in 1988 at the age of 27, he had short-circuited the American art scene not only shifting the expectations of visual arts at the time but highlighting the racial injustices of a biased society. Quite instantly, he reached a profound popularity, selling his works by the dozen, to collectors and celebrities for thousands, often before the paint had even dried. He was an enigma. Categorically appealing to all those who came into his orbit, he became a bona fide celebrity of the 1980s street and club scene. A time when artists were as newsworthy as rock stars or movie stars, Basquiat, with his compelling, considered speech style, his cool, freeform Congo dreadlocks and his unique, frantic, dramaturgical work ethic, was a thing of fascination. By 1987 he had covered Time magazine (dressed in Armani, under the headline “New Art, New Money”), walked the runway for Comme des Garçon, partied at institutions like the Mudd Club, created an experimental noise band called Gray and mixed in crowds that included Madonna, Bianca Jagger, Keith Haring and Andy Warhol. For those that knew him, like his close friend, contemporary and bandmate Michael Holman, his allure was rapturous.

“You have to understand, and this would have been evident to anyone at the time, Jean-Michel was miles ahead of everybody—intellectually, creatively, aesthetically, spiritually,” says Holman. “He was just an ancient man in a young man’s body. He was like a self-realized being, like some kind of Dalai Lama of art.”

Holman, himself, was an original part of the burgeoning New York downtown scene. Bringing hip-hop artists, graffiti artists and performers together, he helped orchestrate an era and locale known for its renegade collaborative nature. It was at Holman’s (along with visual artist Stan Peskett and hip-hop pioneer Fred “Fab 5 Freddy” Brathwaite) infamous Canal Zone party in 1979, that he first met a teenage Basquiat. The artist had recently been revealed to be one-half of Brooklyn’s mysterious SAMO graffiti tag. An acronym he and friend Al Diaz fused from the phrase “same old s**t,” the duo sprawled intriguing, facetious writings like “SAMO for the so-called Avant Garde” and “Stop the train of thought SAMO” across subways and buildings in New York. Holman was interviewing the newcomer on the night and recalls becoming flustered in his presence.

Read more: Ms Puiyi has Had Enough of Your Labels

“I think it was actually a passive-aggressive thing,” says Holman. “I was part of throwing the party which was all about showing art, but I didn’t have any art in it. So, I kind of felt jealous. That’s why I was being somewhat passive-aggressive [towards Basquiat]. Then later on, when I went up to apologize, he said, “That’s okay. You wanna start a band?” I was like, yeah, sure! We started Gray that night.”

This kind of impulsive energy proceeded the artist and it spilled into his work. His was a frenetic method. Painting at all hours, his explosive, mural-like pieces bore the absurdity and gruesomeness of the Cubists with the anarchistic rebellion of New York urban scrawling. Artistically inspired by the two-dimensional anthropologies of Picasso and Matisse as well as the potent abstracts of Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, his works were an exploration of personal and systematic tribulation. Graphic figures, often with the ominous or condescending halo of a king’s crown were portrayed via emotionally charged layers of paint, scratchy, thick brush strokes and vigorous, unsettling lines. He’d been fascinated by Henry Gray’s 19th Century medical tome Gray’s Anatomy (also inspiring his band’s name) since his mother gave him a copy to read while he recovered in the hospital after being hit by a car when he was 8 years old. Its anatomical diagrams came to find a core intellectual and emotional theme throughout almost all of his works.

“He recognized at a young age, when he went to a museum and looked at all the works and saw names like Warhol and Picasso, the power and the fame and the importance that came with it,” says Holman. “He did the math and knew that he had this in himself. It was just a matter of timing for him—to put it together, to find his voice, his style and what he could master that was clever, unique and impactful. I think he knew what was happening and what would happen with his name today.”

Read more: Director of Tiger Stripes on Making it to Cannes Film Festival

Systematically, too, Basquiat found purpose in generating topics of segregation, racism, poverty and historical abstraction in his works. He adorned Black male figures with his signature three-pointed crown motif and sketched in cryptic word-plays like “origin of cotton” (in reference to the slave trade) and “Hollywood Africans 1940” (the year Hattie McDaniel became the first African American to win an Academy Award for Gone with the Wind). He also intentionally painted rough strikes through many of these phrases in a conscious effort to draw attention to them. He spoke about viewers being more likely and compelled to read something if it seems to be crossed out.

Basquiat is honoured by almost all that met and worked with him during his lifetime as well as those who follow his posthumous legacy. In a piece for Interview magazine in 2014, Madonna spoke about her romantic relationship with Basquiat in the early 1980s. As a close friend of the artist conglomerate — a group inclusive of Pop Art greats Keith Haring and Andy Warhol — the singer reflected on his work style.

“I remember getting up in the middle of the night and he wouldn’t be in bed lying next to me; he’d be standing, painting, at 4 in the morning, *this* close to the canvas, in a trance,” Madonna said. She also told Howard Stern, around the same time, that he “would not stop doing heroin” and that “when I broke up with him he made me give [the paintings he gave me] back to him. And then he painted over them black.”

Since his death, his name has developed a kind of otherworldly reputation, as though he prophetically planned out his career and life, predicating it into the venerable, poignant period it’s now referenced as. His fame was a supernova, but it’s a celestial opinion many art critics, even galleries at the time, refused to acknowledge. Late art historian and controversial critic Robert Hughes famously wrote an essay in 1988 for The New Republic about Basquiat’s quick, inflammatory success. Entitled “Requiem for a Featherweight” he flouted Basquiat’s celebrity appeal and relegated his popularity to the obsessive, exploitative nature of American pop culture.

At the same time, similar opinions were held by establishments like the Museum of Modern Art in New York when they refused to purchase his works, dismissing them as insignificant and pieces of graffiti. As a result, even now, all Basquiat works on display at the MoMA are loaned, rather than owned.

Jean-Michel Basquiat came from a middle-class background, the son of a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother, he was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. He developed an early love for art and culture thanks to his mother taking him regularly to the city’s museums. It’s suggested that he was a particularly gifted child, learning to read and write earlier than most, although he found it difficult to concentrate on regular schooling. By the age of 10, Basquiat’s parents separated and not long after his mother was committed to a psychiatric institution, something that had a considerable, long-lasting effect on him. He and his two sisters were then raised by their father but at the age of 15, Basquiat ran away from home. He spent time couch-surfing, sleeping on benches in Washington Square Park, partying and experimenting with drugs. In the years following, when his art began to draw attention, it’s reported that many of his supporters were surprised to find Basquiat had not, in fact, come from poverty, and were shocked even further to see his father arrive at events driving a Mercedes.

Basquiat lived by rapid means, moving from place to place as a young artist. Two of his girlfriends, Alexis Adler and painter Suzanne Mallouk have often spoken about living with him. About his working methods, his passion for creating and his excessive life. They recalled his intense love for jazz music, for women and, of course, drugs. When Basquiat found financial success, his apartment was said to be littered with opened bottles of expensive wine and plates of uneaten gourmet food. It was a revolving door for young rappers, artists and street kids, (whom he supported with financial donations) and a hang for everyone who was anyone. As success grew, it’s suggested he chased away buyers he didn’t like, especially those deliberating over the aesthetics of his work and, despite accessing fame, he resented the spotlight, the constant attention and the camera crews that came with it. From here Basquiat struggled with addiction and began to deteriorate from dependency. At the time of his heroin overdose on August 12, 1988, he was living in Warhol’s loft on Great Jones Street, Manhattan. Warhol had died the year before at the age of 58. Today, there are still murals dedicated to them on the front wall—one reads “Kings Live 4Ever.”

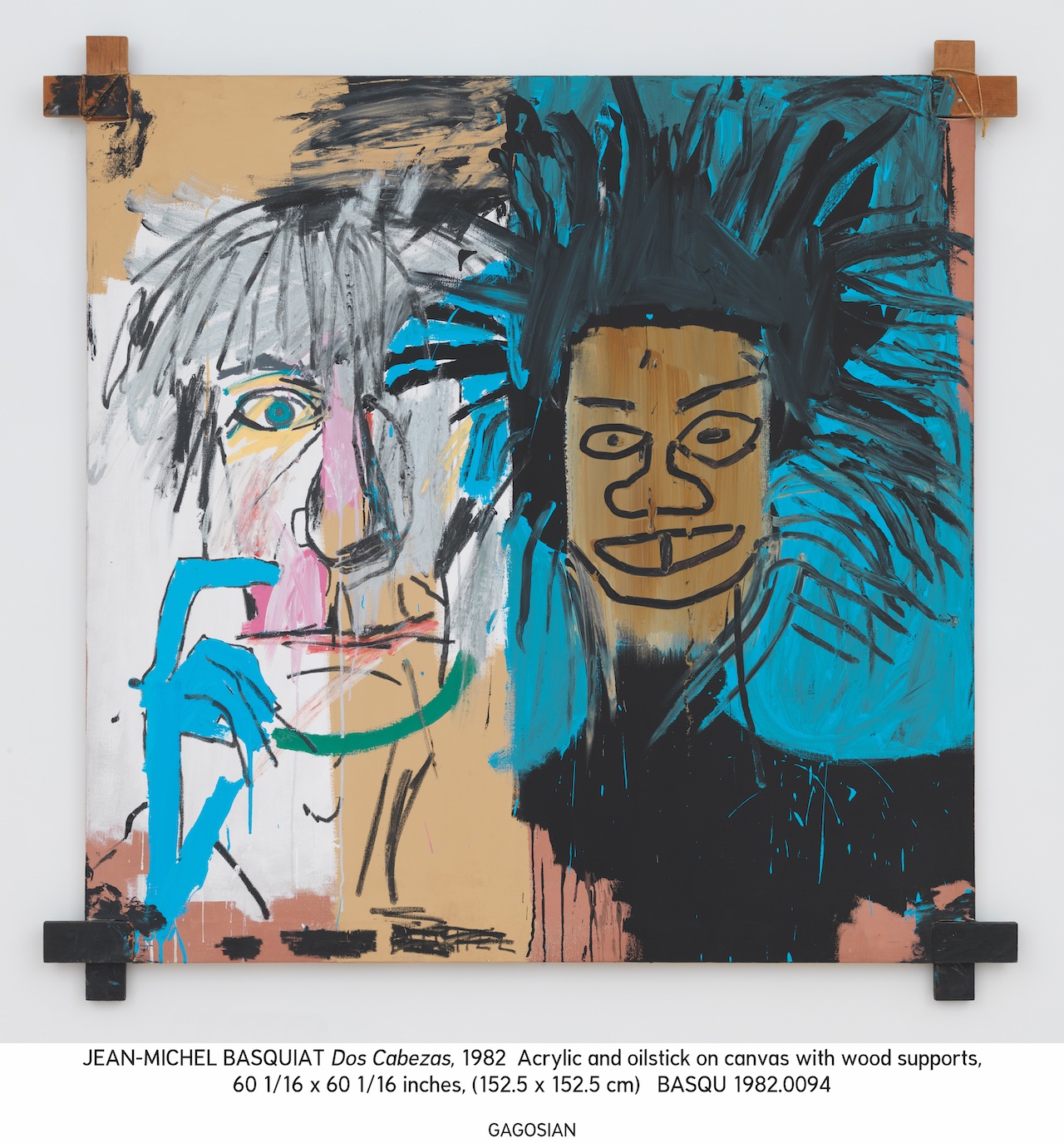

Before their untimely deaths, however, Warhol and Basquiat worked on what was to become one of the most iconic art collaborations in history. A tennis match of creativity the artists sent works back and forth, imposing their identifiable styles onto the same large canvases. Pieces that fused the cartoony, commercial nature of Warhol with Basquiat’s irreverent deconstruction, the collection was divisive and deliberate. Upon unveiling in 1985 however, the works, which included side-by-side self-portraits and monolithic corporate logos layered with Basquiat’s line drawings, became one of the most controversial cultural topics of the time. Keith Haring described it to be a “conversation occurring through painting, instead of words,” with Basquiat explaining “Andy would start one [painting] and put something very recognizable on it, or a product logo, and I would sort of deface it.” It sent reviewers into a frenzy and the public even more so. Now, some 37 years later, the Louis Vuitton Fondation in Paris has become the host of a retrospective. Titled Basquiat X Warhol. Painting Four Hands, features over 160 rarely-seen artworks by the pair and will run until August of this year. The curator of the exhibition, Olivier Michelon, mused the ongoing obsession with the Basquiat and Warhol dichotomy.

Read more: Preserving National Heritage the Cambodian Way

“This story is fascinating because it shows two people, known for their signatures, willing to do things together, even to the point of blurring the lines,” he says. “Warhol said that their most successful works were those where you didn’t know who did what. I think it’s not so much in terms of style or imprint but in the production of a final painting. Warhol places a background that allows Basquiat to make a figure exist in an amplified way. Basquiat crossed a Warhol by revealing what was under the surface. Seeing this painting is like participating in a conversation where the words compose sentences continuously, but then are remixed by the artist and your own eyes.”

The exhibition opened in April with an exclusive performance by Jay-Z. The rapper, who has only appeared publicly a handful of times in the last few years, was an auspicious guest to honour the event. He’s a known Basquiat enthusiast, often referencing the artist in his music (“It ain’t hard to tell, I’m the new Jean-Michel”), fielding regular physical comparisons (especially the style and shape of his hair) and in 2013 was revealed to be the anonymous buyer of Basquiat’s acrylic and oil-stick skyline silhouette Mecca — that he snapped up for a cool $4.5 million.

In 2021, Jay-Z again set the Basquiat underworld alight when he and wife Beyoncé posed in front of rarely-seen piece Equals Pi. It was part of a commercial for jewellery company Tiffany & Co., with the artwork believed to be owned by the corporation. The piece features a distinctive aqua background, one easily comparable to Tiffany’s own robin’s egg shade of blue. Some Basquiat die-hards declared the image a misuse of his work, while others applauded the unique and expansive platform.

Read more: Alien Superstar! Beyonce’s Renaissance Tour Wardrobe is Putting Couture in Discotheque Culture

In the years since his death, the Basquiat-ification of future generations has been impressive. He has become a kind of cultural deity, recalled and revered for his artistic genius, but even more so for what he personally represented. In December 2017, his masterpiece Untitled was purchased by Japanese collector and retail magnate Yusaku Maezawa for $110 million. This record sale made Basquiat the highest-selling American artist of all time. For comparison, Edvard Munch’s The Scream sold for $119 million in 2012 and Pablo Picasso’s Le Rêve sold for $155 million in 2013. This month, two more Basquiat originals will go under the hammer. The unusually monochromatic piece Now’s the Time, an ode to jazz and legendary saxophonist Charlie Parker, is expected to reach around $30 million, while his 12-foot wide El Gran Espectaculo (The Nile), owned by designer and avid art collector Valentino Garavani since 2018, is likely to go for $45 million.

But despite the exceptional value of his original pieces, his street ubiquity continues to grow. It’s a disconnect that doesn’t seem to affect the credibility of his name, nor his wider interest. Today you can find Basquiat-printed clothing and merchandise everywhere. Reebok and Doc Martens are stitched with his signature crown motif, DC and Converse trainers in painterly Basquiat prints, high-fashion collaborations with labels like Junya Watanabe and Etudes as well as niche skateboard brands with his artworks across their decks. If Basquiat the artist was big business, then Basquiat the brand is even bigger. But does celebration on masse preserve and promote his notoriety or begin to dissolve it?

“I’m torn. I’m torn,” says Holman. “I don’t know if it’s putting his integrity at risk, or if it’s making him bigger and more and more important. It certainly doesn’t seem to have hurt his market. I guess it’s the world we are in today—two realities that stand very much a part—the licensing and the over-exposure, [versus] the art market for his work. Obviously, the value of his original art remains because the amount he created is finite.”

In a radio interview with Holman back in 2007, the film producer and musician who still resides in New York City and performs with Gray (they have a new album due out this year) lamented the lack of Black artists in the fine art world. He talked about Basquiat being a unicorn and a pioneer, and how he broke through a predominately white world. In turn, he said he believed that over the next couple of decades, this breakthrough would lead to a pattern of change. That people of colour would have greater representation in the visual arts. So, now that the future is here, was he right?

“Every important gallery has Black artists now. Male, female, gay, straight, it doesn’t matter. Every important gallery has Black artists from America, from Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa and from all over the world. Everything has changed,” he concludes. “And I really believe it’s almost singularly because of Jean-Michel Basquiat. I mean, how many people, like gallery owners or financiers or high executives or whatever might have said, well, s**t, if Basquiat did what he did, why shouldn’t I give this next guy or girl a chance? Because do I want to be the person who denies the next Basquiat?”

When the titillating topics of value, money and celebrity enter the realm of an artist’s mythology, it can quite quickly eclipse their reality. That is, that a real person existed, one who strived to create art, make a difference and express emotion. A real person that experimented with creativity, who made mistakes, took risks and cut open a path for so many others to follow. But perhaps this is the kind of person that was never meant to be real, not long-term. A person destined to fade in order to make way for iconography. As Basquiat himself once prophetically declared “I’m not a real person, I’m a legend.”

“He was a genius and everyone knew it,” says Holman. “There was just something about him. And listen, I met a lot of famous people, everyone from Mick Jagger to Martin Scorsese to Gloria Steinem [but] I’ve never met anyone like Basquiat. And I feel a little bit emotional telling you this right now. I’ve never met anyone as brilliant as he was. I’ve never met anyone who made me feel like I was in the presence of a self-realized being. He had that aura.”

This story first appeared on GRAZIA International.